When the Spreadsheet Thinks You’re a Slacker: Conscientiousness, Compliance, and the Politics of Measuring Virtue

What happens when your refusal to salute the wrong flag gets you labelled ‘low conscientiousness’? From anti-Nazi saboteurs to student rebels with homemade bombs, we follow the absurd logic of surveys that confuse compliance with character - and ask why some economists and moral psychologists keep mistaking obedience for virtue.

Anweshan Ghosh

8/10/20259 min read

The Moral Messiness of Our Time - And Why the Data Thinks It’s a Decline

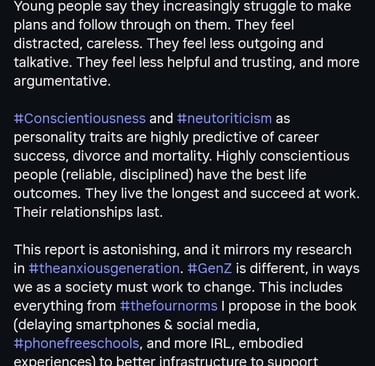

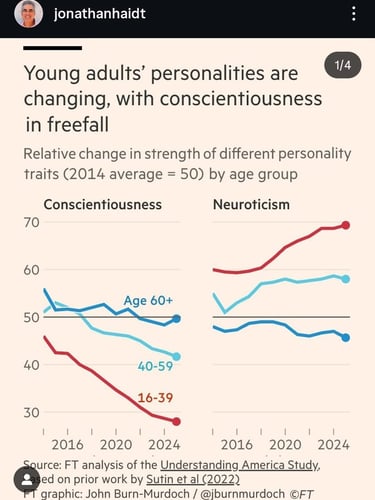

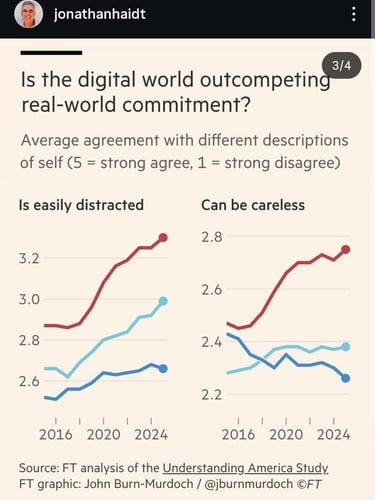

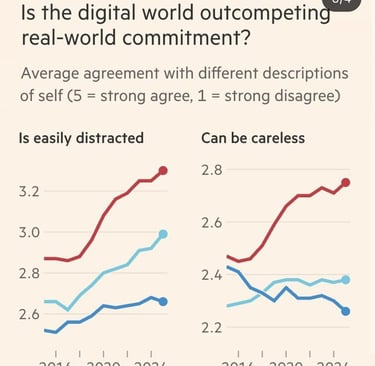

There is a certain kind of headline that works best over tea and biscuits in the morning - a headline that flatters the reader with the sense of being one of the last sensible people left. Recently, one of them came courtesy of the Financial Times, bearing the subtle alarm of a doctor telling you to go on that daily run: Young Americans are losing conscientiousness.

The piece had numbers, charts, and a smooth line of argument. Over the past decade, the USA's youth had - according to the data - become less reliable, less orderly, less diligent. They were less likely to keep things neat, follow through on plans, or be “reliable workers.” And if you glossed over it while rushing through your breakfast, you might have imagined bedrooms littered with laundry, unread emails stacked up like unpaid bills, and an entire generation with dyed hair shrugging its way into moral decline over avocado toast and Starbucks coffee. Dead-eyed, disobedient and dramatic.

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist whose recent work reads like a long letter from a concerned uncle about the state of civilisation, nodded along to the figures. Haidt has been arguing for years that the mental health of the young is in trouble, that smartphones, social media, and cultural drift have left them fragile and distracted. Here, it seemed, was the personality data to confirm it.

But what if the problem is not in the youngsters - but in the ruler we’re using to measure them?

Politeness Won’t Save You from the Gestapo

The numbers in question come from the Understanding America Study (UAS), a large, ongoing survey that periodically asks people to fill out standard personality questionnaires. In this case, it’s a version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI), a well-known tool in psychology for measuring broad traits: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Conscientiousness, in the Big Five, is supposed to capture things like self-discipline, dutifulness, orderliness, and perseverance. But here’s how it’s actually measured in the UAS. Respondents rate how much certain statements describe them:

“Does a thorough job.”

“Tends to be lazy.”

“Does things efficiently.”

“Makes plans and follows through with them.”

“Is a reliable worker.”

“Keeps things neat and tidy.”

“Tends to be disorganized.”

“Is easily distracted.”

On the face of it, these seem like perfectly reasonable items. Who would object to being thorough, reliable, and efficient? But take a closer look, and a certain picture emerges. These items lean heavily toward order-following behaviour - the kind of conscientiousness that makes a good mid-century civil servant: punctual, neat, predictable, a cog that turns when the clock strikes.

Nowhere in these questions is there an item that asks, “Acts on moral convictions even when it is inconvenient” or “Persists in doing what is right despite pressure from authority.” There is no room for conscientiousness as integrity. In fact, in many historical contexts, the people who would have scored high on “follows through on plans” were the very ones following through on orders we now regard as unconscionable.

Authoritarianism for Beginners

The psychologist Erich Fromm saw this problem early. In The Authoritarian Personality, he and his colleagues mapped how traits like dutifulness and orderliness could be co-opted by repressive systems. The “authoritarian character,” he argued, might be both cleanly dressed and morally bankrupt — capable of filing every form in triplicate while ignoring the human suffering it produced.

Fromm’s deeper point was that there is a difference between conscientiousness as compliance and conscientiousness as conscience. One keeps your sock drawer organised; the other compels you to risk your job to report the sock factory’s child labour. Our surveys, unfortunately, don’t always bother with the distinction.

When the Psych Tests Meet Protest Signs

This blind spot matters, because history is full of moments when people of principle would have scored abysmally on these scales.

Take the White Rose movement in Nazi Germany. These were students — messy-haired, inconsistent in their studies, sometimes unreliable in the trivial sense — who spent their nights printing anti-Nazi leaflets. To their university supervisors, they may have looked distracted, perhaps lazy; they missed classes, failed to keep tidy schedules. On a Big Five form, “Is a reliable worker” might have earned a “disagree.” But in moral terms, they were paragons of conscientiousness.

Or consider the anti-Vietnam War protests in the United States. The young people who left their dorm rooms and jobs to march were denounced as “undisciplined” and “irresponsible” by politicians and newspaper editorials. They skipped lectures, ignored work shifts, slept in unwashed tents. On the BFI’s orderliness items, they’d have looked worse than their peers who stayed home. But their refusal to quietly uphold a policy they believed to be unjust was a form of conscience the scale cannot capture.

Teenage Revolutionaries and the Wrong Personality Type

The same pattern runs through the Indian freedom struggle. In 1930, the Chattagram Armoury Raid was led not by seasoned soldiers but by students barely out of adolescence—Anand Gupta was seventeen, Lokenath Bal twenty-one, most others in their early twenties—alongside their schoolteacher, Surya Sen. Like Bhagat Singh or the trio of Binay, Badal and Dinesh, they remind us that resistance has often been the work of the young, those yet untrained in obedience, for whom the moral duty to defy outweighed the instinct to comply. Boycotts and strikes were, in the imperial ledger, symptoms of irresponsibility and laziness. In the neat handwriting of colonial administrators, the conscientious citizen was the one who paid taxes and kept the trains running on time. The troublemakers, the disorganised, the “unreliable,” were the ones who ended up on the right side of history.

The Science of Siding with Power

Psychologists who study the Big Five have long known that conscientiousness has subcomponents. There’s orderliness - the preference for structure, tidiness, and predictability. And there’s industriousness - the capacity for hard work and persistence. Both get rolled into the single score you see in the FT chart.

Here’s the catch: orderliness correlates, across many studies, with political conservatism and preference for authority. High scorers like rules and routines; low scorers are more comfortable with uncertainty and change. In peaceful, functional democracies, orderliness might be harmless or even beneficial. But in times of institutional rot, it shades easily into blind obedience.

This is where Haidt’s reading of the data is worth pausing over. His work often laments the erosion of shared norms, civility, and common ground - values that overlap with the orderliness facet. It’s not that this view is wrong, exactly, but that it risks equating the decline of deference with the decline of decency. The young people who bristle at following through on plans they don’t believe in - or who won’t keep things neat for an employer they think is exploitative — are not necessarily less conscientious in the moral sense. They’re just answering the questionnaire honestly.

Why the FT Saw What It Saw

The Financial Times, for its part, loves a story in which social change shows up in neat, downward-sloping lines on a graph. It reassures its more cautious readers that there is an identifiable problem, quantifiable and therefore solvable - ideally by nudging society back toward the habits of an imagined golden age. The problem is that the habits being measured here are not timeless virtues but context-bound behaviours. “Makes plans and follows through” sounds like a moral good until you ask whose plans and toward what end.

There’s an almost comic mismatch between the nostalgia implied in the coverage and the world in which young people now live. A generation for whom steady jobs are rarer, housing is precarious, and institutions often appear either incompetent or corrupt is unlikely to treat “is a reliable worker” as a neutral prompt. Reliable to whom? For what purpose?

From Dreams to Deadlines

Another wrinkle: personality traits do shift with age. Conscientiousness tends to rise as people settle into long-term jobs, marriages, and parenting. Comparing 22-year-olds today to 45-year-olds - as if both were in the same stage of life - is like comparing seedlings to oak trees and complaining the seedlings aren’t shady enough. The UAS does track the same people over time, but the headline figures blend across ages, letting life-stage differences blur into “generational decline.”

Add to this the gig economy, delayed marriage, and a more fluid work-life structure, and you get fewer opportunities (or incentives) for the kind of behaviour the scale rewards. If your job changes every six months, your follow-the-plan-through scores may dip even if your commitment to your values is unwavering.

Rebelling Against the Rulers of the Mind

If we really want to know whether young Americans are losing moral fibre, we should be measuring more than punctuality and tidiness. There are scales for moral identity, for moral courage, for willingness to resist unjust authority - but they’re absent from the UAS battery. We could ask:

“Acts on principles even when costly.”

“Speaks up when something seems wrong, even if others stay silent.”

“Keeps commitments to people, not just to procedures.”

My suspicion is that on these measures, the picture would be far less dire. The activists like Greta Thunberg working ceaselessly against climate inaction, the whistleblowers like Edward Snowden who believe that the state should be under scrutiny instead of the citizens, the ‘academic pirates’ like Alexandra Elbakyan who dream of the everyone having access to knowledge, the humanitarians like Francesca P. Albanese working at great cost to bring the world to a consensus on stopping a genocide, the students like Umar Khalid willing to risk the wrath of a state at great personal cost to ensure that every citizen has their rights - they might score low on “keeps things neat” and high on “will not stand idly by.”

Messiness as a Democratic Virtue

In Haroun and the Sea of Stories, the Guppee army - led by General Kitab - is famous not for its discipline but for its endless arguments. Soldiers debate every order, question every strategy, and break into side discussions about the ethics of the mission or the quality of the tea. To an outsider, it looks like chaos. To the Guppees, it is the essence of their strength: disagreement sharpens ideas, trust allows dissent, and collective ownership of decisions makes them fight harder when the moment comes. Mudra, the defected Shadow Warrior from Chup, is astonished by this culture. He comes from a land of silence and obedience, where orders are swallowed whole. In Gup, he finds something alien yet strangely resilient - a living proof that messiness can be a democratic virtue.

Perhaps the hardest truth for lovers of tidy data is that a healthy democracy is noisy, inconsistent, sometimes a little dishevelled. People who always follow through on every plan are as likely to keep bad plans alive as to execute good ones. The same orderliness that keeps a society stable in good times can keep it stagnant in bad ones.

This doesn’t mean order is worthless, only that it’s not the whole story. A generation less inclined to be “reliable workers” for systems they don’t trust might be exactly what a fragile democracy needs. They may miss more deadlines, yes. But they might also be the ones to pull the brakes when the train is heading somewhere it shouldn’t.

A democracy without noise, contradiction, and a little disorder is not a democracy at all - it’s a showroom. Khattam-Shud, the villain in Haroun and the Sea of Stories, seeks to poison the Ocean of the Streams of Story, leaching away its swirling colours and mingled currents until every tale is the same dull shade. In the same way, the urge for perfect order in public debate can bleach away the “liquid tapestry” of voices that makes it worth having at all. If we try too hard to keep discourse tidy, we risk draining it of life.

The Perils of Being Perfectly Well-Behaved

The FT’s chart will continue to circulate; Haidt’s diagnosis will continue to resonate with those who feel the ground shifting under their feet. But if we want to tell the truth about conscientiousness, we have to see it in two lights: the tidy desk and the clean conscience.

One is easy to measure with a few survey items. The other requires looking at what people do when keeping the desk tidy means ignoring the fire outside the window.

In our own age of institutional distrust and democratic erosion, it may be that the decline the data shows is not in conscientiousness at all, but in unquestioning compliance. If so, perhaps we should learn to live with a little chaos - at least while the house is worth keeping in order.